Jacob Z. Hess, Ph.D.

First published on the EternalCore Conference website (Join us this coming Friday and Saturday, March 29-30 in Salt Lake City for a gathering to explore a “God-Centric Mental Health” – what that looks like, and what it could mean for those suffering).

Note: Suicide is an inherently difficult topic – especially for those families who have been impacted by this tragedy. It’s precisely the enormous pain of suicide that arguably calls for a wide-ranging discussion of anything that could potentially help reduce the numbers. The purpose of this article is to raise one possibility not widely considered – partly because it involves an intervention largely embraced as central to solving the problem. This article does not constitute medical advice and should not be used to guide individual care decisions. No changes to any medication regimen should be made without supervision from a physician – especially since research confirms that dosage changes are one of the times where risk for suicidality is heightened. I believe that everyone is doing the best they can to solve this societal problem, and that we need to make sure there is space in our public discussion for all possibilities (including unpopular ones) so we can make more progress. All feedback will be appreciated.

Like so many others, I’ve lost loved ones to suicide. The heartbreak this causes for so many families has prompted enormous prevention efforts and a wonderful new Church website dedicated to helping raise awareness.

The most obvious question that comes up is why? What was it that led this individual…to that? Although there will always be some uncertainty involved in this profound heartbreak, thousands of studies documenting various risk factors for suicide make it clear that no single cause is responsible, as much as hundreds of overlapping contributors.

As suicides keep rising, another “why” question arises: Why have the numbers been going up? This brings up other conversations about social media and the opioid epidemic, along with other unique cultural and economic factors that have shifted markedly in the last decade or two. Shifting views on sexuality have also been rightly discussed as potentially playing a role in growing distress, although there are substantial disagreements about how to make sense of that influence.

The why question we’re not talking about. There’s a third “why” question that is far less obvious and rarely discussed: Why do these numbers continue to rise, even when we are doing so much to decrease them?

In Utah, the legislature has passed many measures on suicide prevention over the years – expending many hundreds of thousands of dollars over the years. And yet preliminary reports have suggested the numbers continue to rise.

Our state is not unique. That same pattern is happening all across the country – with many millions of dollars spent nationally in suicide prevention, with suicide numbers at their highest rate yet, across most every age group.

So, what’s going on? Is it time to talk about that?

Remarkably, there is very little discussion about this third question. Rather than critically exploring what about our current efforts may not quite be working, we seem to largely take for granted that these numbers would be rising even more without our efforts. But what if that’s not true?

I focused my dissertation research on antidepressants at the University of Illinois, and have explored long-term outcomes for depression now for over 15 years. You’d think when we’re talking about something so universally important (and so excruciating to so many), that we as a society would be open to any possibility – and all hunches. But my experience has been that this is simply not true – with some possibilities and hypotheses met with incredible, even visceral resistance. This is especially true of possible explanations that bring scrutiny to ideas or practices widely embraced as good, meaningful and healthy parts of our lives – and perhaps even promoted as crucial answers to suicide itself.

If you feel suicidal, please reach out to a loved one or trusted professional. And if you have no one to talk with, please contact a prevention line available in your country. For instance, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline in the U.S. can be reached 24 hours everyday here: 1-800-273-8255. And here is a list of other suicide prevention hotlines available in countries all around the world.

Getting more people into treatment. Over the last two decades, certain scholars and doctors have reassured us that if we get more people into treatment the suffering of mental health problems will decrease – and along with that, the tragic suicide numbers.

To be clear, getting help of any kind is so often a really important thing. And in some cases, that message has led people to seek out therapeutic guidance from a counselor or mental health professional. It’s clear, however, that in the larger majority of cases, it’s medical treatment that people reach out for first, as reflected in statistics over the last two decades. For instance, a 2011 report released by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) showed that the rate of antidepressant use in this country among teens and adults (people ages 12 and older) had increased by almost 400% between 1988–1994 and 2005–2008 – leading to estimates of one in every 10 Americans taking an antidepressant.[1] A 2013 report likewise found approximately one in six U.S. adults reported taking a psychiatric drug, such as an antidepressant or a sedative.[2] And a 2006 review found 12 percent of adults reporting that they were on an antidepressant,[3] with SSRIs the third most prescribed drug in America since 2005.[4]

And what has been the result? Despite these kinds of dramatic increases in access to psychiatric care, there is a great deal of evidence that the burden of mental/emotional distress has worsened and increased during precisely this same time period.

And yet despite this, once again, even with an expanded mental health conversation in society today, we have paid little attention to these uncomfortable correlations. Instead of talking about these disconcerting possibilities, the primary, overriding attention in our national conversation about mental health continues to go in the same direction: how can we get more people into treatment?

It’s time for a bigger conversation.

Seven Lines of Evidence Worth More Attention in Our Public Conversation about Suicide

In what follows, I will summarize seven different lines of evidence related to the broader question of why suicides have increased in the very moment that we’ve been working so hard to reduce the numbers. Each of these distinct areas of evidence highlight the degree to which this aspiration for simply “getting more and more people into treatment” may have, inadvertently, become part of the very problem we’re all earnestly trying to allay.

More specifically, these different lines of evidence converge around the same point: that there is a significant subset of patients who, when taking an antidepressant (especially at the beginning of treatment, or when a dosage is changed), experience uncharacteristic, distinct, and sometimes dramatic increases in suicidal ideation and behavior.

That idea might be challenging for you – especially if you’ve found these medications beneficial at some point in your life (either for you or someone you are helping). Please understand: this is not an anti-medication exploration. It’s an inquiry about best-practice and informed consent – exploring the boundaries of who, what, and when someone is most vulnerable to these adverse affects and what thoughtful, selective medication usage looks like as part of an integrative package of care.

Given the striking extent to which rates of suicide have risen in parallel to rising rates of antidepressant treatment, however, I would propose this as a conversation we really cannot avoid having – not if we really want to get to the bottom of this and find ways to reverse these numbers.

Importantly, the information that follows does not constitute medical advice – nor does it replace any advice your or someone you love are receiving from professional helpers, whether that is a therapist or doctor. Under no circumstances should someone stop taking medications quickly or without appropriate supervision. That can be dangerous – so please only take steps carefully, gradually and with the support of trusted people around you.

I’m sharing this below in hopes of helping expand the professional and public conversations about suicide, so we can take additional steps to prevent this tragedy for many more people.

I. Case Studies & Clinical Observations. When Prozac came out, there were early indicators of some concern in this vein. But it wasn’t until the 1990s where documented, clinical observations first started to appear. For instance, one respected researcher, Martin Teicher, wrote: “Six depressed patients free of recent serious suicidal ideation developed intense, violent suicidal preoccupation after 2-7 weeks of fluoxetine [Prozac] treatment. This state persisted for as little as 3 days to as long as 3 months after discontinuation of fluoxetine [Prozac]. None of these patients had ever experienced a similar state during treatment with any other psychotropic drug.”

A few years later, Teicher and colleagues reported on one young girl who began cutting herself after taking a high dose of Prozac, with self-mutilation described as “incessant.” And yet, once again, after this patient tapered off Prozac, her self-destructive behavior and suicidal thoughts disappeared.

As other similar case studies like this emerged, a pattern became evident, as Dr. Teicher himself summarized at a follow-up FDA hearing: “the reason why I believed that we were dealing with a drug-emergent effect is because the symptomatology that [patients] developed during the time they were on fluoxetine was unlike anything they had experienced prior to or following.”[5]

One of the FDA researchers, Dr. Newman, a member of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs and Pediatric Advisory Committee that helped review evidence of suicide in youth, noted that it was persuasive to observe that “several of these cases involved patients who had shown no hint of suicidality before beginning treatment with the drugs and who had been given these drugs for indications other than depression, including migraine headaches, nail biting, anxiety, and insomnia.”

II. Qualitative Evidence. In many of these stories that started to emerge, the reality is there was no researcher or doctor involved to monitor or take careful notes about what happened. Instead, family members, friends, neighbors and journalists grappled to make sense of a tragedy after the fact.

Several different efforts to aggregate and gather these stories have taken place (for instance, here, here and here) – most of which reference this older, original archive in different ways. These stories represent a second line of qualitative evidence – most of which are either newspaper reports or self-reported narratives from friends or family members. For instance, one father wrote:

In 2009 my son, who had never been depressed in his life, went to see a doctor over insomnia caused by temporary work-related stress. He was prescribed Citalopram [Celexa], and within days he had taken his life. At my son’s inquest, the coroner rejected a suicide verdict, but delivered a narrative judgment, citing Citalopram [Celexa] by name as the “possible cause.”

By my count, there are about 1,000 stories of suicide in the original archive of someone taking their life soon after starting an antidepressant or changing a dosage. Additional hundreds of other stories are gathered on the other sites. For those trying to understand the extent of this evidence, I’d encourage you to dive in and explore the databases cited above to familiarize yourself. I’ve done that myself – reading and analyzing the themes across many of these stories. There are three things that stood out to me, most prominently:

- First, similar to the clinical observations mentioned above, in many cases the suicidal behavior that emerged in these narrative accounts was completely out of character for people who were otherwise reported by family to be moving forward in generally productive, successful lives. Often, these individuals had simply reached out to a physician during a challenging time – for instance, involving unusually high stress.

- Secondly, when a marked psychological deterioration started to occur after starting treatment, neither the surrounding families and friends or the person taking the medication had any idea it might be connected to the medication. It was common to hear from family afterwards, “I had no idea that this could be a possible side-effect – not at all.”

- Third, when early problems started to emerge with the antidepressants, the professional response typically involved (a) encouraging people to increase the dosage and (b) attributing any difficult side-effects (like new panic attacks) as a reflection of additional pathology being uncovered – “now we know you have an anxiety problem as well” or “psychosis might be something we need to pay attention to.” It seems clear that even medical professionals have had remarkably little awareness of the possibility of antidepressant- induced suicidality. Many simply haven’t known.

Although substantial, these kinds of databases have typically been written off by people as “just anecdotal” (aka, not worth much). I disagree. Even one story ought to matter – even if it, admittedly, it cannot provide definitive answers. But when hundreds and even thousands of stories start to establish similar themes, we ought to be paying careful attention.

Despite these many stories, the possibility of a connection between suicide and antidepressants continues to largely be met by quizzical looks and incredulous responses. For many, the idea that taking an antidepressant could worsen your mood and invoke suicidal thoughts or feelings seems ridiculous – after all, they’re antidepressants, right?

To any who see this possibility as somehow ‘out there’ or hard to believe, let me remind you: it’s on the package! Rather than some outlier idea, these are risks acknowledged on every package of antidepressants, ever since the black box warning was mandated following FDA hearings and a comprehensive review of the evidence.

In spite of these warnings, once again, most people (doctors, therapists, patients and families) are still functionally unaware of this possibility – which makes discussions like this important. Let’s now move on to a third line of evidence – namely, the accepted, acknowledged side-effects associated with all antidepressants.

III. Established Side-effect Profiles. Despite the lack of awareness regarding possible drug-induced suicidality, there is more general awareness about the more varied side-effects that can arise, including emotional distress that is new. Let’s talk about three more commonly discussed examples.

1. Akathisia. This is a fancy word for “inner restlessness.” On the original patent for Prozac, akathisia was labeled as “one of its more significant side effects.” Listen to how neuro-psychologist Dennis Staker describes his own drug-induced akathisia for two days: “It was the worst feeling I have ever had in my entire life. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy.”

Another individual characterized it as “ach[ing] with restlessness, so you feel you have to walk, to pace. And then as soon as you start pacing, the opposite occurs to you; you must sit and rest. Back and forth, up and down you go … you cannot get relief.”

In one of the case studies mentioned earlier, Rothschild and colleagues note:

Three patients developed severe akathisia [inner restlessness] during retreatment with fluoxetine [Prozac] and stated that the development of the akathisia made them feel suicidal and that it had precipitated their prior suicide attempts. The akathisia and suicidal thinking abated upon the discontinuation of the fluoxetine [Prozac].[6]

2. Amotivation/Apathy. In what they refer to as an “amotivational syndrome” associated with the frontal lobe, Dr. Jane Garland and colleagues report on five cases of youth prescribed antidepressants who came to experience a unique level of apathy and lack of motivation, sometimes accompanied by disinhibition. In each case, these symptoms were linked directly to dosage and were reversible after tapering back the child. However, given (a) the similarity to depression’s own symptoms, (b) a child’s lack of insight in appreciating this and (c) the fact that the onset of this lack of motivation comes later on in treatment, Dr. Garland warns doctors about the strong likelihood of missing this possible adverse effect, and the need for carefully monitoring children especially.[7]

This phenomenon of drug-induced amotivation/apathy has also been studied and documented over the years in adults on antidepressants as well, with 11 different studies provided in the references.[8]

3. Hyper-Activation/Disinhibition. Compared to the decreasing motivation just described, a seemingly opposite effect has been noted by researchers for years and acknowledged by the FDA as early as 2004 (see FDA report here). In 2003, Faeda and colleagues wrote about “treatment-emergent mania (TEM) or increased mood-cycling following pharmacological treatment” in youth, a subset of which experience “prominent suicidal behavior.”

And in 2006, Goodman and colleagues investigated one of the mechanisms behind suicidal behavior leading to the black box warning, noting that “during the course of SSRI treatment, some children may experience an ‘activation syndrome’ characterized by agitation, insomnia, irritability, brittle mood, and other signs of hyperarousal that, if unrecognized, could conceivably foster suicidality.”

Dr. Shauna Reinblatt and colleagues summarized their data in 2009 documenting the frequency of this concerning pattern “activation” involving specifically impulsivity, insomnia, or disinhibition. Compared to 23 youth in the placebo group (where 1 experienced symptoms of restlessness), 10 of the 22 youth (45%) in the treatment group experienced this kind of heightened activity. Other studies have found between 10 and 50% of kids experiencing these same “activation” symptoms. On average, these symptoms emerged anywhere between week 1 and week 8 (with week 4 being the average).

Whereas some have attributed these manic episodes to a latent bipolar disorder, other case studies confirm the frequency of this occurring as a drug-induced effect. For instance, Dr. Aggarwal reported in 2011 on a boy (without any present risk factors for bipolar patterns) who experienced “increased psychomotor activity, euphoric affect, racing thoughts, grandiose ideas, and inflated self-esteem” upon starting an antidepressant. Once the prescription was ended, these symptoms went away.

Understandably, physicians face a similar confusion as patients, at times, in determining how to assess what they are seeing (for instance, see this new article, “Primary Care Practitioners May Mistake Irritability as Bipolar Disorder in Youth“).

Okay, so it’s one thing to hear a case study, or newspaper report, or side-effect profile, but what do the actual studies say?

IV. Observational/Correlational Evidence. There are at least four major correlational/observational studies within the last decade and a half looking directly at this question – each summarized briefly below (with links available to the actual study if you’d like to dive deeper).

1. 2006 Columbia University Study. A research team lead by Dr. Olfson in the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University compared Medicaid beneficiaries across the country who had similar patient profiles, except for differences in whether they received antidepressant treatment or not. While noting no significant difference in adult suicide attempts or death, they noted, “In children and adolescents (aged 6-18 years), antidepressant drug treatment was significantly associated with suicide attempts and suicide deaths.”[9] (It’s worth noting, here, that while the correlation being explored here shows up frequently for adults as well, the established research is strongest for children and teens).

2. 2015 FDA Study. Umetsu and colleagues reported in 2015 on a large epidemiological study based on data from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System database, with analyses confirming clear associations between SSRI treatment and suicidal and self-harm events. As with other studies, these associations were stronger in the under 18 group, compared with older participants.[10]

3. 2016 Danish Study. In an observational study of 392,458 Denmark medical records, Christiansen and colleagues found “a significant overlap between redeeming a prescription on SSRIs and subsequent suicide attempt.” They found, specifically, that “the risk for suicide attempt was highest in the first 3 months after redeeming the first prescription.”[11]

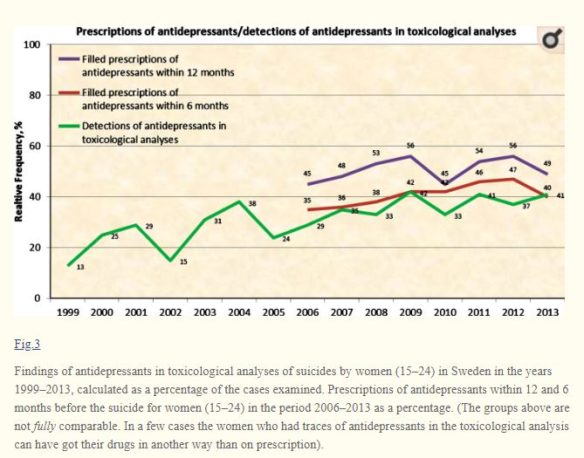

4. 2017 Swedish Study. This study analyzed 483 suicides from young women in Sweden between 1999-2013 (representing 93% of all confirmed suicide for this subgroup) – with a focus on looking at whether these women had received antidepressants within 6 and 12 months before the suicide.

[I have tried and failed to obtain this same data in the United States. One of the leading sociologists in our own home state of Utah shared private frustration with me recently that, unlike Europe, there is resistance to release this data in the U.S., even to researchers].

So, what do you find when you carefully examine this kind of data? Dr. Larsson summarizes what she found: “The previous assumptions that treatment with antidepressants would lead to a drastic reduction in suicide rates are incorrect for the population of young women. On the contrary, it was found that an increasing tendency of completed suicides follow the increased prescription of antidepressants.”

The researcher continues, “This analysis shows a covariance between increased prescription of antidepressants and an increasing trend in the number of suicides among young women” – adding, more specifically, “This study shows that an increasingly larger proportion of young women, who later committed suicide, has the last few years been treated with antidepressants, prior to and at the time of the suicide.”[12]

Once again, wide perceptions that those who commit suicide are “undertreated” was found to be incorrect in this rigorous national analysis covering 15 years.

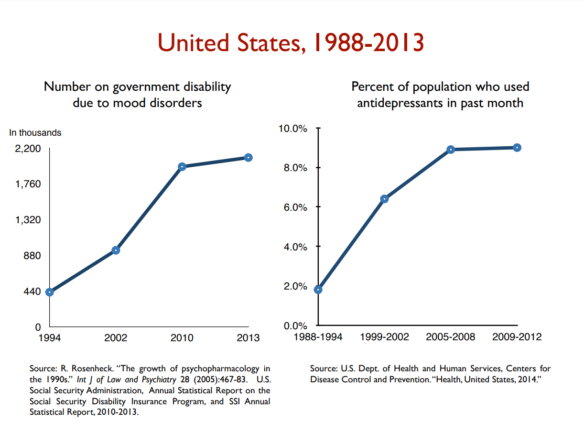

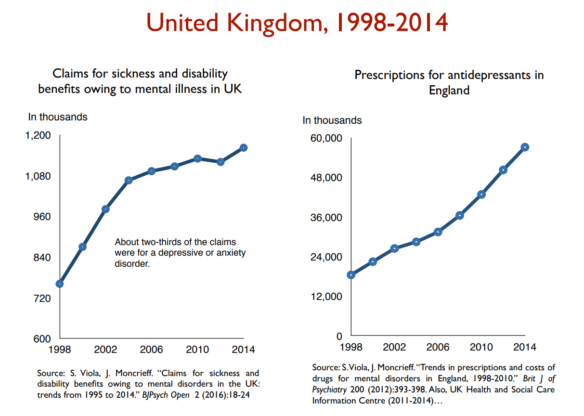

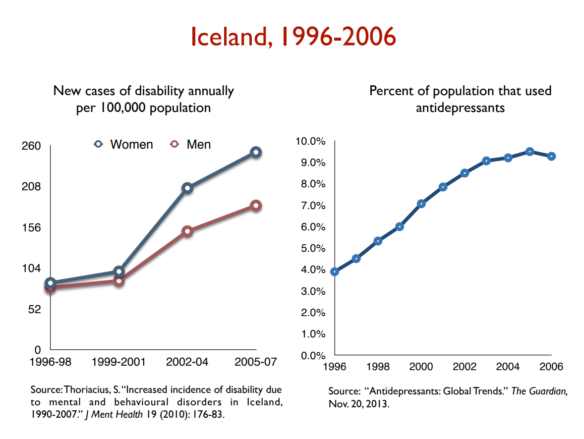

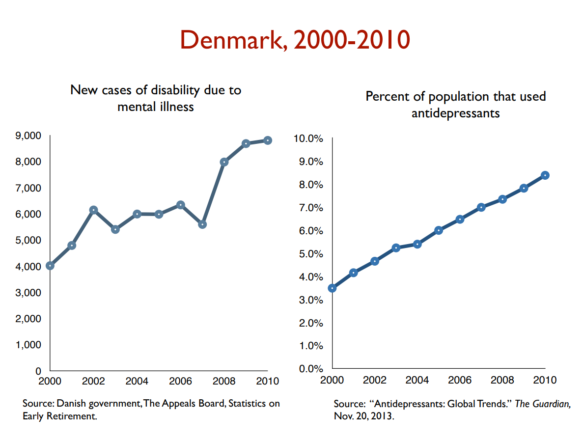

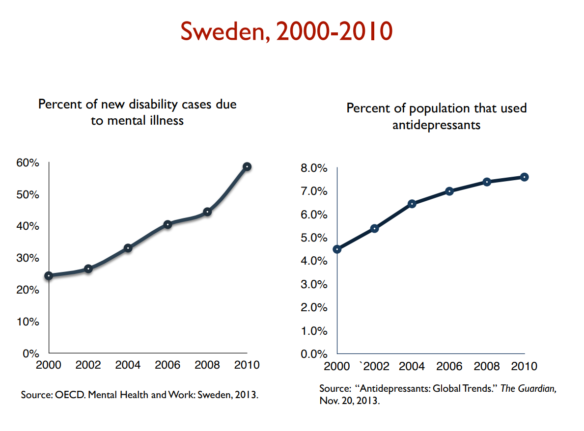

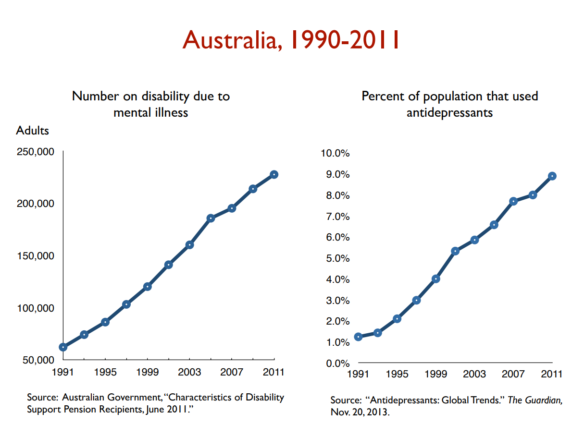

When we look across larger periods of time, it’s also hard to not notice consistent correlations across different countries between antidepressant use and deteriorating mental health (credit to Robert Whitaker):

Now, in fairness, correlation studies can still only tell us so much. There are also correlation studies dubiously claiming that an increase in pornography yields an associated decrease in rape – and that percentages of certain religious groups in a given state are associated with teen suicide. Although recognizing their worth as one form of evidence, we need to hold any correlational claims carefully, given the many other potential variables involved.

Given that complexity, one of the obvious next steps is to pay greater attention to studies that control for more of these variables.

V. Controlled Studies. In the last decade and a half, I’m aware of at least four comprehensive reviews looking at suicidality and antidepressants – each briefly summarized below.

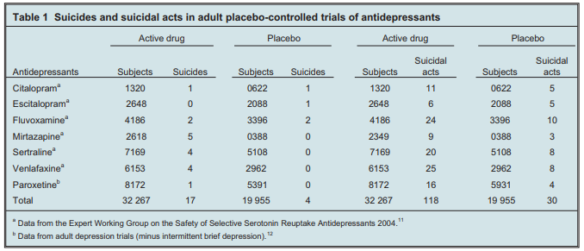

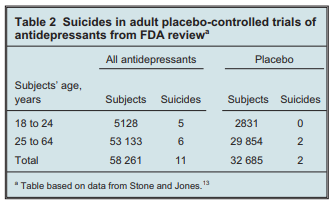

1. 2004 British Review. In a review of suicidal behaviors posted by British regulators, they found a 2.62-fold increase in completed suicides and a 2.4-fold increased risk in suicides and suicidal acts for youth taking antidepressants, compared with placebo (see Tables 1 and 2 for raw numbers).[13]

2. 2005 Canadian Review. This research team gathered all randomized-controlled trials between 1967 and 2003 in a comprehensive review of 702 of studies submitted to government regulators on suicide risk (totaling close to 87,650 patients studied). The key finding from this exhaustive review by Fergusson and colleagues was a significant (more than twofold) increase in the odds of suicide attempts for patients receiving SSRIs compared with placebo or other interventions.[14]

3. 2006 U.S. Review. In the United States, the FDA deliberated over a similar review specific to pediatric meta-analysis data and suicide. You can find details of that comprehensive write-up (here – all 131 pages), and published formally by Hammad and colleagues in 2006.[15] In lay language, the individuals in the studies who took the drug were about twice as likely to have been actively thinking about suicide, or made a suicide attempt, or made preparations to die by suicide, when compared to those receiving a placebo.

As this research team went on to state, “the observed signal of risk for suicidality represents a consistent finding across trials.” They summarized the conclusion as follows: “when considering 100 treated patients, we might expect 1 to 3 patients to have an increase in suicidality beyond the risk that occurs with depression itself owing to short-term treatment with an antidepressant.”[16]

While that may seem small to have 1-3 people with extra suicidal risk per 100, given the millions of people taking antidepressants nationally, it starts to multiply quickly.

4. 2016 Danish Review. In a more recent 2016 review, a research team in Denmark analyzed data from 70 trials (64381 pages of clinical study reports) involving 18526 patients submitted to European and UK regulators.[17] Similar to other studies, they found a doubling of the risk of suicidality for children and adolescents taking antidepressants.

Referring to this doubling of suicidality among those taking antidepressants, Dr. David Healy writes: “This is not an isolated finding, but is the case for almost every single antidepressant studied.” He adds, “No longer can we simply blame the disease: the drugs appear to be playing a role in making some people more likely to take their lives.”

That phrase some people is really important here. Dr. Phillip Hickey summarizes:

No one…is suggesting that a large proportion of people taking antidepressant drugs kill themselves….What is being contended, however, is that these drugs are inducing strong suicidal urges in a relatively small proportion of individuals who had not previously had thoughts of this kind, and that some of these people are succumbing to these urges, and are taking their own lives. This is … very important, and it warrants investigation even if it involves only a fraction of one percent of the people taking the drugs. To dismiss these widespread and credible contentions on the basis of the dogmatic insistence that the drugs are wholesome, or that the individuals were probably suicidal to begin with, is simply unconscionable.[18]

I agree with Dr. Hickey. Even if this affects only a percentage of people taking antidepressants, given the growing percentage of adults (and youth) now taking them – it seems deeply wrong to not to take these patterns seriously.

There are two final lines of evidence that further corroborate these claims.

VI. Long-term Studies. Most of the data examined above focuses more on short-term results and outcomes – with a specific focus on early stages of prescriptions as especially risky. For those who have examined the longer-term trends of people who take antidepressants for many years, there are other patterns that emerge, however – worth considering.

In particular, I am aware of 22 different studies looking at long-term outcomes on anti-depressants, often in comparison to people who never went on the drugs. Every single study I’m aware of shows a similar pattern of worsening outcomes long-term, with more depression for those who stay on the drug, when compared to those who don’t. If you’d like to see for yourself, you can review summaries of all of the 22 studies here, as detailed in a previous article: “Long-term Anti-Depressant Outcomes We Can’t Ignore Anymore.”

VII. Historical Evidence. Lastly, there is also historical data that confirms these same patterns above. In particular, when you compare historical patterns before antidepressant treatment became common, and afterwards – you see increasing chronicity in depression and a pattern of people not getting better over the long-term (at least not at any depth).

If you’d like to review this for yourself, check out this summary of Robert Whitaker’s writing about this here: “Historical Details Before the Anti-Depressant Era”.

For those interested in reviewing the evidence connected to the unique risk of antidepressant-induced suicidality in youth, click here for a more in-depth piece.

And that’s it: Important evidence pertinent not just to the question of suicide – but to perhaps the most interesting, under-explored question of all: why have suicides been increasing even when we’re doing so much to decrease them?

Could this evidence provide an explanation for that question?

I think so. In fact, I don’t know any other plausible hypothesis that best explains the data available on that specific question. It appears that there is a subset of people who do not metabolize SSRI medications adequately and for whom the blood levels build up to a point that they act in uncharacteristic, even tragic ways (one of the leading theories for all of the evidence above).

Some would argue that these adverse effects for a subset are worth it (or perhaps a necessary sacrifice) given the larger benefits for a bigger group. If there were no other known ways to reduce depression or suicidality, that would make sense. But there are literally hundreds of other things we could try! So at a minimum, this raises questions about our predominant pattern of turning first to medical treatment.

If nothing else, I hope this review also makes clear how confusing it feels to those of us familiar with this research literature to hear prominent psychiatrists insisting that the central problem we’re facing is that not enough of our teens and adults are accessing antidepressant treatment.

In light of the literature reviewed above, that statement feels irresponsible

– and even potentially damaging. The fact is this: we’ve expanded treatment access for two decades now. And things are worse than ever before when it comes to depression, anxiety and suicide. Rather than continue to follow the same decades’ old arguments about under-treatment, it’s time to carefully rethink our fundamental approach.

I’m convinced it’s urgent to have a more forthright, honest conversation about how well people are truly doing long-term. And when it comes to positive, proactive steps, here are some to consider that could reduce the risks associated with the above patterns:

- Stop talking about mental health, and depression, in particular, in a way that could inadvertently invoke additional despair – aka, hinting towards a life-long burden. This separate article summarizes that well: Ten Simple Things We Can Do Immediately to Reduce Suicide: A Zero-Cost Public Mental Health Proposal

- Encourage families to explore other options prior to initiating antidepressant treatment. As Dr Timothy Spruill asks, “despite the fact that the Cochrane review of the evidence confirms the effectiveness of counseling for depressed patients, why is it that consumer use and physician referral for counseling continues to decline?” Alongside management of symptoms, it’s important to bring more intervention focus to root contributors. Dr. Tomi Gomory, a professor of social work at Florida State University, told me, “A focus on chemicals can become a way of avoiding the harder conversations about changes needed in the social environment.”

- Don’t ignore the black box warning. Contrary to the popular dismissals and warnings about the suicide risk, it’s time to stop ignoring the clear risk, particularly for youth and adolescents prescribed these drugs.

- More robust informed consent. Speaking of informed consent, Dr. Tomi Gomory told me in personal correspondence, “we need a fully transparent discussion of the pro’s and cons. Providers rarely, if ever, identity all the adverse effects and reactions.”

- Closer monitoring, especially of children and adolescents. The most common recommendation to emerge from all the studies I have reviewed was a consistent plea for physicians (and parents) to watch more carefully signs of worsening. This comes up over and over and over in the research articles: Dr. Leslie and colleagues call for “generally at least weekly contact during the first 4 weeks, with specific visit intervals specified after those 4 weeks.” Shauna Reinblatt and colleagues call for “Close monitoring for [adverse effects], not only when initiating SSRI treatment but also throughout dose titration,” as a recommendation “for early identification of activation.” Dr. Jane Garland and colleagues warn for careful monitoring of children, especially given the many ways we might miss them, including “(a) the similarity of some adverse effects to depression’s own symptoms, (b) a child’s lack of insight in recognizing them this and (c) the fact that the onset of this lack of motivation comes later on in treatment.” Christiansen and colleagues recommend “systematic risk assessment in the period after redeeming the first prescription.” Dr. Olfson states that “These findings support careful clinical monitoring during antidepressant drug treatment of severely depressed young people.” And Umetsu and colleagues add, “Children and adolescents should be closely monitored for the occurrence of suicidality when they are prescribed SSRIs.”

- More support for gradual, carefully tapered reductions. Help patients taper off if and when they feel ready. In many cases where tapering happens, however, physicians have received little training on safe and effective discontinuation. For those doctors seeking an expanded skill-set, there was a great training that happened in 2017 (recorded and available here) – and another in 2018. Luckily, there is also a growing amount of powerful information to guide individual patients, families, and professionals on the gradual, personalized, careful, and managed tapering process people need to be successful (slow and mindful enough to manage withdrawal effects). This is best done with professional oversight. Check out Laura Delano’s Withdrawal Project as a great place to find more guidance.

- Reconsider the risk/benefit profile. As noted above, it’s also time to have a more serious conversation about the true risk/benefit profile of antidepressants for youth, removing the distorting influence of industry (more details on that research here).

- Stop telling patients they need to be on antidepressants life-long. This is happening a lot, with patients experiencing various mental/emotional conditions – including with children. Please stop telling people this, and help them appreciate the possibility of tapering off one day if-and-when the time is right (and with appropriate supervision). As I’ve written and spoken about extensively, the life-long treatment message can be, for some, such a despairing message for people to hear – and undoubtedly, has contributed to some people reaching a place of lethal despair (see these essays, these videos + this class).

Don’t ignore this. Please don’t. What I’ve raised may be uncomfortable to consider – but not nearly so uncomfortable as the excruciating pain of families who have experienced this unspeakable tragedy.

May the infinite worth of these precious lives compel us to not turn away from possibilities we don’t like. And may the great value of each individual lead us to put every possibility on the table – including those that may demand some potentially significant revisions to our usual way of doing things.

Finally, may God help us to be courageous, discerning and humble in this conversation, for the sake of those who are hurting the most (including me!) I welcome feedback and critical questions from others who may disagree, but have equal passion and interest in reducing these numbers.

Notes:

[1] From that same report: “23% of women in their 40s and 50s take antidepressants, a higher percentage than any other group (by age or sex). Women are 2½ times more likely to be taking an antidepressant than men.”

[2] The new data comes from an analysis of the 2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), which gathered information on the cost and use of health care in the United States. Moore and Mattison found that nearly 17 percent of adults in the U.S. reported filling at least one prescription for a psychiatric drug in 2013.

[3] In addition, 8.3 percent of adults were prescribed drugs from a group that included sedatives, hypnotics and anti-anxiety drugs, and 1.6 percent of adults were given antipsychotics, the researchers found.

[4] This is true since at least 2005, (see “Astounding increase in antidepressant use by Americans,” October 20, 2011, Peter Wehrwein, Contributor, Harvard Health)

[5] Details of the FDA hearing are summarized in Bass, A. (2008). Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower, and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial. Algonquin Books

Emphasis there and in the case study report are mine. Here is the first reference: Teicher M.H., Glod C., Cole J.O. (1990). Emergence of intense suicidal preoccupation during fluoxetine treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry;147: 207-10.

And here is their follow-up study: Teicher MH, Glod CA, Cole JO. (1993) Antidepressant drugs and the emergence of suicidal tendencies. Drug Safety, 8(3):186-212.

[6] Rothschild A.J, Locke C.A.(1991). Reexposure to fluoxetine after serious suicide attempts by three patients: the role of akathisia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry;52: 491-3.

[7] Garland, E.J. & Baerg, E.A., (2001). Amotivational Syndrome Associated with Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Children and Adolescents, Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 11(2), 181–186

[8] Here are studies exploring the same phenomenon in adults, in chronological order (from 1990 to 2016): Marin 1990, Diagnosis of apathy; Goldsmith 2001; Barnhart 2004, SSRI apathy syndrome; Reinblatt 2006, SSRI-induced apathy; Wongpakaran 2007, SSRI-induced apathy in elderly.; Moret 2009, Apathy, lack of motivation, frontal lobe syndrome; Sansone 2010, Apathy and indifference; ; El Mallak 2011, chronic depression dysphoria caused by antidepressants; Makris 2012; Perroud 2012; Read 2014, Antidepressant-induced apathy and indifference; Cartright 2016, long term deterioration [Credit – Peter Breggin]. Related to this, one colleague, Al Galves, who has spent years working with people facing these challenges, reminded me about a piece in Peter Kramer’s book Listening to Prozac, where he observed some patients on Prozac having “lost their conscience.” They just didn’t care as much. He continued:

I also have read that most of the psychotropic drugs cause emotional blunting, an impairing of the ability to process emotions. That stuck me because, when a patient of mine tells me s/he is thinking out killing herself or himself, I ask what the advantage of that would be. They pretty much all say something like “It would be all over. I wouldn’t have to deal with this stuff anymore. The pain would be gone.” Then I ask them what would be the disadvantage of it. Everyone says it would be devastating for their friends and family. If you take away that concern and caring you are increasing the risk of suicide.

[9] Olfson M., Marcus S.C., Shaffer D. (2006) Antidepressant Drug Therapy and Suicide in Severely Depressed Children and Adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 63:865-72. Two years later, Dr. Olfson and colleagues again found confirmation of this trend with additional analyses.

[10] Umetsu, R., et al., (2015), Association between Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Therapy and Suicidality: Analysis of U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System Data, Biological Pharmacy Bulletin, 38(11), 1689–1699.

[11] Christiansen, E, Agerbo, E. Bilenberg, N., & Stenager, E. (2016). SSRIs and risk of suicide attempts in young people – A Danish observational register-based historical cohort study, using propensity score. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 70(3)

[12] Larsson, J. Antidepressants and suicide among young women in Sweden 1999–2013. (2017). International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine, 29(1-2): 101–106.

[13] Expert Working Group on the Safety of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Antidepressants 2004. Safety of antidepressants [Internet]. London (GB): Medical and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency; 2004 [cited 2006 May 13]. Available from: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/ idcplg?IdcService=GET_FILE&dID=1391&noSaveAs=1&Rendition=WEB. 12.

GlaxoSmithKline. Paroxetine adult suicidality analysis [Internet]. GlaxoSmithKline; 2006 [updated 2006 Apr 5; cited 2007 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.gsk.com/media/paroxetine/briefing_doc.pdf.

Stone M., & Jones L. Clinical review: relationship between antidepressant drugs and adult suicidality [Internet]. Washington (DC): United States Food and Drug Administration; 2006. Table 16, p 26; Table 18, p 30. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/ 2006–4272b1-index.htm.

[credit for both tables to Healy, 2009]

[14] Fergusson, D., et al. (2005). Association between suicide attempts and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal, 330(7488): 396.

[15] The primary outcome, which was labeled “suicidal behavior or ideation,” contained three elements: Suicide attempts, and/or Preparatory actions towards imminent suicidal behavior, and/or Suicidal ideation. The overall risk ratio (drug vs. placebo) for the three elements combined was found to be 1.95 (95% CI, 1.28 – 2.98). The risk ratio for suicidal behavior (first two items) was 1.90 (95% VCI, 1.00 – 3.63).

[16] (Emphasis added). See also Breggin 2003 and Newman 2004 for additional analyses of the data available at that time.

[17] Sharma,, T., Guski, L.S., Freund, N. & Gøtzsche, P.C. (2016). Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports. British Medical Journal, 352

[18] Philip Hickey, “Suicidal Behavior After FDA Warnings,” July 7, 2014

Very well done Jacob. Thank you.

I have been on Paxil for about 15 years, and it has made my life much, much better than it was.

The first thing drug-related that I would associate with suicide is the government’s and medical establishment’s apparent position that leaving millions of Americans in unrelieved chronic physical pain is a small price to pay to squelch the opioid epidemic.

Thank you, Brother Clerk! No doubt many feel similarly and would attest to benefits like your own experience. This piece does not deny that – nor suggest that medication cannot have a valuable place in healing. I’m focusing primarily here on the subset of people for whom there are surprising, adverse effects – and raising the question as to whether this may help explain the increase in suicide statistics even when we’re doing so much to try and reduce them.

I’m with Clerk. I have been on Citalopram for 10 years and it changed my life. Frankly if I had to go back to that racing mind I had before the medicine, I would take my own life.

Articles and studies like this scare me. Are you going to pull the medicine? I used to take a cox 2 inhibitor for pain. Remember those? Yeah, they were extremely effective – they also got pulled because they supposedly caused heart attacks in some people. When you say “may the infinite worth of these precious lives compel us to not turn away from possibilities we don’t like”, what are you suggesting?

I appreciate the article. I’m not competent to say what should or should not be done, but I can intuitively understand that an over-focus on treatment might cause the problem to get worse (speaking very broadly and looking solely at numbers, not at any individual situation). For any individual situation where I was asked for advice, I think I would want to recommend treatment.

To what degree psychiatric drugs should be viewed as a true last resort? Similar to antibiotics, is it possible that too much of a good thing is leading to benefits in many cases while simultaneously adversely affecting the population.

To what degree does variability in therapist capability with regard to patient treatment have a greater impact on patient outcomes than other health treatments (for instance hypertension medication for high blood pressure)?

Which demographic groups are more at risk to contemplate/commit/attempt suicide when taking psychiatric drugs? Is a comparatively simple study too determine and situate the prospective patient within these groups. Then reasonable effort can be made to mitigate at risk groups.

In my experience there’s definitely a lot more trial and error and throwing various drugs and dosages at the problem to see what sticks. I think the treatments can be lifesaving. I think it’s inevitable that we end up treating psychiatric drugs as a miracle pill that “fixes” the issue, when it’s highly probable in many cases it either didn’t help or made things worse.

What the ultimate course of action is, is difficult. But my personal experience suggests that best patient outcomes are not just in taking medicine and trying to do business as usual, but in real life changes in time with loves ones, work, personal activity, and even diet. The drugs can be a part of that, but even they are the only part of that, negative outcomes are much more likely.

Lily’s comment about self harm if she doesn’t get her medication is either sadly flippant or indicative of real personal issues. Suicide just shouldn’t be discussed or considered as an option like that. How many more mass shootings would we have if those who were disappointed by society threw around comments like, “well if they don’t change their ways I’m going to have to go on a shooting spree to draw some attention to the issue”.

Suicide is no more victimless than murder. Just because the perpetrator and the victim are one, does not make it less tragic, destructive, cruel, and damaging for society.

I realize that’s rather harsh and personal, but the statement of contemplating suicide if you don’t get your way is a really harsh thing to say and put forth a an example.

I’m referring to simply asking the question, Lily – and having the conversation. My experience is most people (professionals and patients) are quite resistant to even broaching the possibility I’ve touched on in this article – namely, antidepressant-induced suidality. It’s hardly discussed as a thing at all.

Within that discussion, clearly, the solutions would be not as clear – since many people have come to rely on their support, even on a long-term basis. But as I note in the recommendations at the end, there are some reasonable things we can do. (If I had to pick one, it would simply be monitoring for this possibility more – watching out for the increase of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in some…*so that* we could take pre-emptive action).

Thanks for the thoughtful response, Libcon. Whereas we currently tend to approach antidepressants as a first resort, I do think – in light of this evidence – they should be last. Other countries have experimented with that, and the results have been positive.

I especially like this question – “Which demographic groups are more at risk to contemplate/commit/attempt suicide when taking psychiatric drugs? Is a comparatively simple study too determine and situate the prospective patient within these groups. Then reasonable effort can be made to mitigate at risk groups.”

One clear answer is YOUTH!!! There is a clearly heightened risk for the developing brain on any psychiatric meds, and yet they have become quite commonplace, I’m afraid. That is a discussion we dearly need to have.

I would push back against taking Lily’s comment as flippant in any way, however. In my interviews with people facing depression, it was common for to hear sincere, earnest belief that life without an antidepressant would be intolerable. Whether that is, in fact, true or inevitable is clearly something to discuss – but the perception and concern is very real and serious. I personally believe that this kind of desperation (I call it “learned hopelessness”) related to the story we tell about depression can prompt a worsening in depression itself over time.

I had a very difficult emergency C-Section delivery after a failed labor with my first child. I also had big problems attempting to nurse the baby. I didn’t get any real sleep for about 4 days. My mental condition was understandably not good. However, when I finally gave the baby a bottle and got some good sleep, I felt much better and was able to start to recover. When I was in the hospital having a subsequent baby the OB making the rounds asked me about my past history of my postpartum mental condition. I told her and she wanted to write me a prescription for an antidepressant just in case. I was rather disturbed at how quickly she was willing to write a prescription. I am sure they can be helpful in many circumstances, but wouldn’t it be a good idea to make sure that other factors are addressed first in a patient. These could be things like making sure they is adequate sleep, diet, exercise or a good daily schedule (especially for teens). Are there family problems, abuse or addictions that need to be addressed? Is there a support system in place for the patient? Do they know basic social skills that help attract friends? I don’t know that a pill will solve those.

I had some roommates that had problems with depression/mental health issues. They also made foolish choices like choosing an abusive boyfriend. If I a boyfriends like her, I would be depressed. It became a chicken or the egg thing. For the record, I also had a roommate who would become suicidal all of the sudden. It was definitely a chemical thing and it was frightening to see. (Mental illness ran in her family.)

This is a good subject to discuss, but a difficult one. I believe that these drugs have a place, but these statistics pose some hard questions. I think it is in order to be more circumspect about prescribing antidepressants to teens. At the very least they should be monitored more carefully. The risks should be recognized.

My teenager just had a teammate unexpectedly kill himself. Its personal to me right now.

I think much of the difficulty is our preference to having a pill fix us without having to go through the pain of working at a more long term solution. Sometimes the long term solution is a pill (I’ve been on effexor for some time, prozac drove me straight to suicidal ideation). It’s much the same with our use of pain clinics; find something to stop the pain now, not necessarily looking to resolve the cause of the pain.

When the choice is a pill that advertises that it will fix everything or something that takes work, time, and money, the pill seems like the easy choice. Besides, suicide happens to other people.

For me, it’s all very personal and real. I have depression and fibromyalgia. My body hurts all over all the time and my mind often feels like it’s floating in mud. Medications might take the edge off for a time, exercise might ease pain after wading through an increase of pain, counselling helps some, doing nothing isn’t always an option.

We need to work our way away from the “easy fix”, work our way back into the time and expense of understanding what does and does not work for each individual body, and most especially lessen (or remove) the stigma of bodily weakness.

My comment wasn’t flippant. I have had suicidal thoughts for as long as I can remember. The medicine goes a long way to help remove those thoughts. I was being blatantly honest: the thought of going back to life before that would kill me – it was that miserable. It wasn’t a spoiled brat comment that if I don’t get what I want I will kill myself.

I believe the OP. I accept all that. But your medical treatment is your personal business. I shouldn’t have to give up medicine that works for me because someone reacts badly to it.

I think part of the problem for those who are unaware of the risk associated with medicine is that when you feel suicidal after starting pills, there is more depression due to the expectation that the medicine should be helping.

Where I live, doctors are quite open about the fact that almost all the medications can *cause* suicidal ideation. Doctors and consumer advocates in my area are proactive about making sure patients know about this. When you dial the central number, the automated greeting specifically directs you to call 911 if this is an emergency. I think the verbiage sometimes (or always?) mentions suicide specifically.

A while ago I was not doing well. As part of treatment, the psychiatrist prescribed one of the common meds that can cause suicidal ideation. It didn’t affect me that way. Insteady, I no longer felt anxious at all, and I stopped caring that I wasn’t getting things done or that I was late or absent to required events (like work).

In my case, I decided that it was worth a bit of anxiety to be able to function as a productive human. Since then I’ve discovered sleep deprivation (having sleep apnea 30+ times per hour) was a contributor. My doctor has me take Vitamin D, which is one of the things that can mitigate depression. And I have discovered the great secret to overcoming anxiety – simply doing the thing that causes stress, rather than feeding the anxiety monster by avoiding.

So, if medication helps, but causes suicidal ideation, realize that this ideation is chemical. Be “mindful” and observe the ideation like the external threat it is. Call for help.

In my case it has also helped to believe that God will be livid if I show up in His space early when I had the option of not showing up early.

“I personally believe that this kind of desperation (I call it “learned hopelessness”) related to the story we tell about depression can prompt a worsening in depression itself over time”

I’ve seen this as well. Reverse aspiration almost.

Lily, please understand that if you really contemplate self harm at the idea of not having your medication and quickly bring that up in a discussion on a personal level, that’s an issue outside of what’s needed to address this social medical issue.

Society can’t be held back from considering issues to a real problem by that very personal and painful, and incorrect (in a moral judgement sense on suicide) statement.

The appropriate counter argument to address, and the way to address it is simply acknowledging who the current treatments are helping and the harm that comes from them not getting treatment.

I don’t believe anyone said they’re taking away your medication. But it seems to me that some people get really upset at the idea (not necessarily Lily here, no bad intent) of medication exacerbating the issue that they drop grenades on the argument to shut it down.

There is a lot of proof these medications cause issues. It’s literally supported by scientific evidence. The assumption was that on the whole the benefits outweigh the risks.

But many in society are wondering that. My impression is that in the best case what inevitably happens is doctors have successful experiences with a type of treatment and gradually treat it as the hammer to every nail, instead of considering screws, glue, rope, clamps or who knows what other methods of attaching things.

It doesn’t further help that there is a commercial interest behind these products. Doesn’t make the companies behind then evil (sure hope not), but the whole concept of bringing a product to market for gain both creates miracles and menaces. It’s made worse that apparently one’s miracle drug is another’s menace.

I’ll just finish writing by pointing out that in doing even the right thing, Father Lehi was lead to a dark and depressive place:

And it came to pass that as I followed him I beheld myself that I was in a dark and dreary waste. (For long time)

The solution was to pray to God to be led to a solution. Not miracle deliverance immediately in his situation. But prayer, revelation, action.

I don’t deny that medicine could be part of the above solution.

I appreciate there are people for whom medication is helpful, but I am with the writer of the above article that we should not forget the people for whom medication is a rabbit hole of nightmares. There are people in my own family who have had adverse reactions to medication, and I feel they have been completely forgotten in the overall conversation about mental health.

One person I am very close to suffered a lot of abuse and neglect in his childhood and was diagnosed with severe mental illness as a teen. What he needed was intense and regular talk therapy to resolve these issues, but for ten years the only treatment he got was 15-minute follow-ups with a psychiatrist asking how the (really terrible!!) side effects were treating him. Talk therapy wasn’t even brought up as an option. I’ve always felt it was highly irresponsible of his doctors to write him a prescription and forget about him for 3 months until his next 15-minute session.

Another person in my family was, I strongly suspect, abused as a child. The abuse was never addressed, even though the effects and symptoms are, to this day, decades later, extremely apparent. Instead she was put on antidepressants at the age of 7. Even with medication, she has always been a hot mess of crazy. She quit cold turkey several years ago because she couldn’t stand the side effects. When she asked about them, the answer was, “It’s either be slightly less crazy with horrible side effects, or even MORE crazy without them.” Given the actual data behind medication, I know now this is a false dichotomy, but it’s still one that doctors continue to sell to their patients. Did her abuse ever get taken care of? No.

Mouse beat me to it.

Childhood sexual abuse is a major factor in significant, perhaps a majority, of mental health issues.

What the CDC calls ACE, Adverse CHildhood Events (or experiences, I forget, just began with “e”), has a 50% correlation to obesity, BMI >30, when combining stats for men and women. That was on the CDC web site, so google it.

My own informal surveys, of just asking people, is when female BMi>40 (“morbid” obesity), the correlation is 90%. (Yes, I do ask aquaintances if they were abused as children, if/when there is an appropriate opening to bring up the subject. And, almost always, they are _appreciative_ that I was able to recognize their symptoms.)

Men have more varied reasons for obesity and morbid obesity, so childhood abuse correlates lower.

This is why bariatric surgery works for a while, but usually not in the long run…. it doesn’t cure the underlying reasons (usually psychological, but sometimes medical) why most people binge eat. The psych reasons/wounds find another outlet, or find a work-around to the surgery.

(Aside: according to stats I’ve read: Transgendered people have a near 100% incidence of childhood sexual abuse. SSA females (lesbians) have 65 to 85% correlation. There’s the tie-in as to why obesity correlates to female SSA. And male homosexuals have a 25% overlap. )

So in essence, much of the so-called “need” for medication stems from, or has roots in, PTSD. Which really isn’t fixed by medication, it mainly requires a form of talk therapy or psychotherapy.

However…. as some explain it, medication can _mitigate the /symptoms/_ in order to _stabilize_ the person, so they can get to the therapist and learn how to process the trauma, and put the demons/memories to bed.

There are also three big causes of childhood sexual abuse, which I think have caused a cascade effect over the last 3 generations:

1) World War II. Veterans with PTSD molesting kids.

2) The Sexual Revolution of the 60’s.

3) VIctims of childhood sexual abuse often (not always, but often) going on to molest.

And, then factor in that PTSD is inherited, not (necessarily) genetically, but it is passed on psychologically via behavior of the parent, which somehow imprints or infuses the effects on the children. E.g.: children of Vietnam Veterans who have PTSD committing suicide, and children of mothers who were abused as children then “inherit” the victim mentality/mindset of victimhood and thereby attract abusers who recognize the victim mindset in them.

It is striking, the frequency with which daughters of rape/abuse victims/survivors who go on to be raped/abused themselves!

And, just to head off the criticism… that is NOT to say that all WWII vets had PTSD, nor that all vets with PTSD molested children.

I must have missed it somewhere, but was there some nexus between the subject matter of this post and LDS thought? I suspect that it must be there, but I admit that I missed it.

From reading the article, in 1 to 3% of people who take antidepressants changing the dosage may make them suicidal. And this might explain why suicide rates are not decreasing in Utah.

Canada suicide rate 10.4, USA 13.7 Utah 22.7 / 100,000 .

Looks to me like Utah has something more going on.

From reading the article, in 1 to 3% of people who take antidepressants changing the dosage may make them suicidal. And this might explain why suicide rates are not decreasing in Utah.

Canada suicide rate 10.4, USA 13.7 Utah 22.7 / 100,000 .

Looks to me like Utah has something more going on.

Geoff-Aus: M* has addressed the subject of Utah suicides for a few years. See the link in this post:

https://www.millennialstar.org/growing-evidence-links-utah-suicides-to-altitude/

Also in that post, scroll down to see the link in Geoff B’s comment; same subject, different study.

The blog’s “search box” on the right side of the mast-head, gives a few more:

https://www.millennialstar.org/?s=utah+suicide

Jacob,

If you are not already familiar with his writings, I would recommend that you browse Dr. Bruce G. Charlton, an LDS-friendly prof in England, and a specialist in evolutionary psychology, and psychopharmacology. (If I recall correctly, he is an MD.)

You may find some new-to-you studies referenced in his blog posts about SSRI’s here:

https://charltonteaching.blogspot.com/search?q=SSRI

He is not a fan of the over-prescription of SSRI’s.

Thank you for publishing this. Mental health issues are taking far too many of our friends and family members. We need better research to help us make better decisions. And better training at recognizing mental illness symptoms so we can get others to help in time.

Thank you for taking the time to share this. I’ve had sexual assault and child abuse survivors tell me stories of getting prescriptions, with no attention to underlying trauma fueling their pain. Let’s have a bigger conversation that invites these possibilities into greater public awareness!

Well said, Meg! A little mindfulness of these patterns would go a long way…heartening to see that perhaps starting to happen more.

I’ve seen what you describe here – and it can be tangibly painful: “when you feel suicidal after starting pills, there is more depression due to the expectation that the medicine should be helping.”