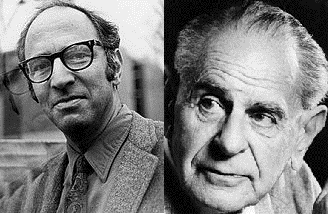

In my last post I finished comparing Popper and Kuhn and again concluded that there really isn’t much difference between the two other than on the issue of Scientific Realism vs. Positivism. That is to say, Popper believes that science actually discovers theories closer and closer to the truth whereas Kuhn believes it becomes more useful over time in ways that we humans wish it to be, but that there is not necessarily some underlying truth to be discovered.

In a previous post I previously considered the advantages of Scientific Realism vs. Positivism. (See also here) Both have pros and cons, but Scientific Realism is the clear winner when it comes to generating new conjectures and theories. If one were to solely believe in Positivism one would never actually believe in their own theories enough to think up new questions/problems to solve and test. The end result would be the stagnation of science.

However, this fact aside, does this mean Scientific Realism is actually true and Positivism false?

Hawking’s Defense of a Positivist View of Reality

Recently Hawking wrote a book called The Grand Design. In that book, Hawking makes a number of controversial assertions. The one that got the most press time – don’t you just love the media? – was the claim that the laws of physics are sufficient to create the universe and that God has no role to play. This is, actually, a very interesting point and one that deserves rigorous criticism – which I’ll gladly give it in the future.

But in reality, this wasn’t the most important challenge that Hawking makes. The really big challenge Hawking makes in his book is that Positivism is actually the nature of reality, not Scientific Realism. We saw in this past post that Hawking is a Positivist.

Continue reading →

Before I disappeared from blogging, I had finished up reposting my Wheat and Tares posts on epistemology (i.e. theory of how we gain knowledge. Good summary of my posts found here. Full series found here, in reverse order of course.) But the truth is that throughout my series, I never really had a single post that attempted to explain what epistemology really is.

Before I disappeared from blogging, I had finished up reposting my Wheat and Tares posts on epistemology (i.e. theory of how we gain knowledge. Good summary of my posts found here. Full series found here, in reverse order of course.) But the truth is that throughout my series, I never really had a single post that attempted to explain what epistemology really is.